Natural Law and the Supreme Court: Catholic Metaphors in Judicial Reasoning

Next time: How do non-Catholic justices reason about abortion, and can we point to a moment where that reasoning was usurped?

A Supreme Court Remade in Far-Right Catholic Ideology

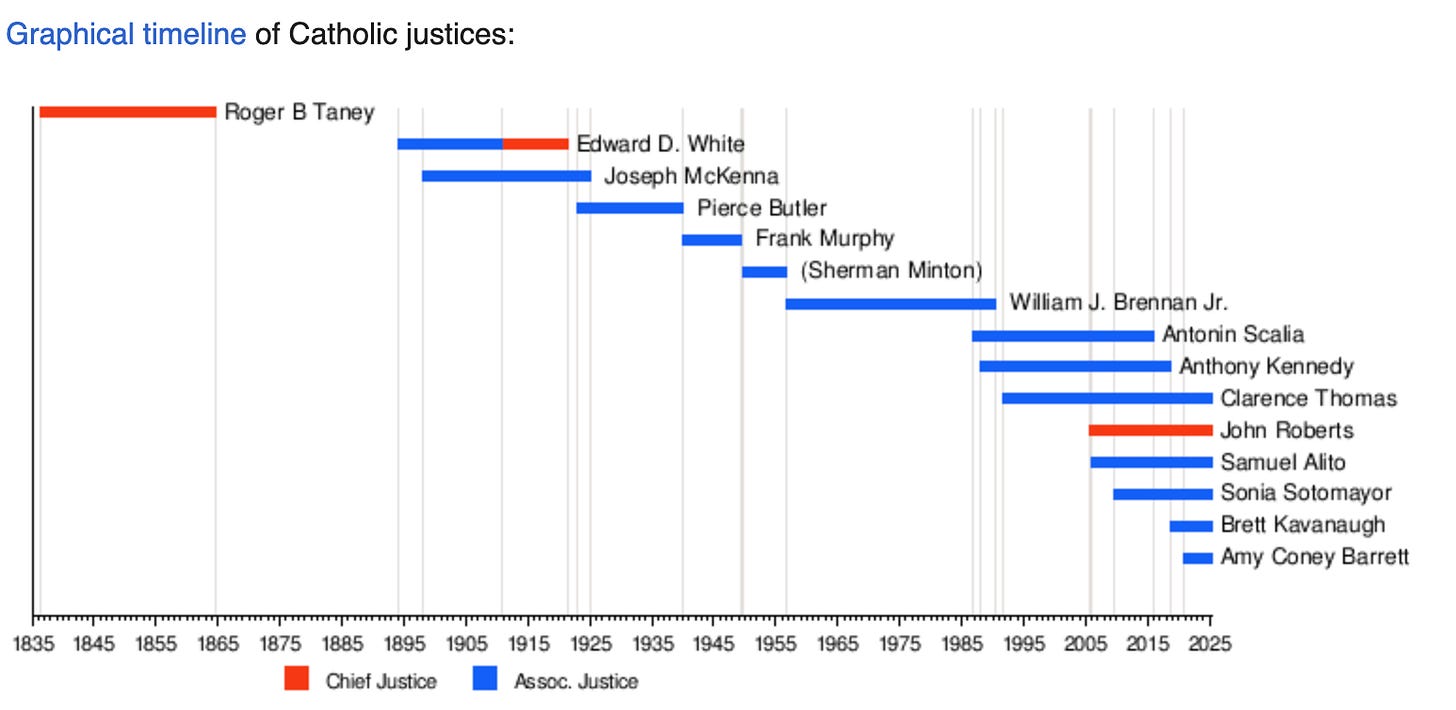

For the first time in American history, seven of the nine Supreme Court justices are Catholic, with six of them aligned with the far-right. This is not a coincidence. It is the result of a decades-long effort by conservative legal networks, including the Federalist Society and secretive Catholic organizations like Opus Dei, to place justices on the Court who embrace natural law as a guiding principle. Their judicial philosophy extends beyond legal interpretation—it seeks to impose a rigid moral hierarchy on American governance, aligning with the broader ideological project of figures like Donald Trump, J.D. Vance, and Elon Musk. This vision, rooted in Catholic natural law, justifies the erosion of individual rights in favor of a supposed higher moral authority. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Court’s abortion jurisprudence, where conservative Catholic justices use natural law metaphors to frame their decisions as moral imperatives rather than legal rulings. Here, I examine how their rhetoric, steeped in religious doctrine, has systematically dismantled reproductive rights and redefined the role of the judiciary in enforcing a theocratic order in recent years.

Natural Law and the Supreme Court: Catholic Metaphors in Judicial Reasoning

The influence of Catholic natural law tradition on the U.S. Supreme Court is more pronounced than ever, with seven of the nine justices raised in the Catholic faith. This tradition, which posits a moral order rooted in divine law and discernible through reason, shapes their legal reasoning—especially on social issues like abortion. Conservative justices frequently employ metaphors drawn from Catholic natural law to justify rulings that reinforce traditional moral hierarchies. These metaphors reveal an underlying commitment to the idea that law is not just a neutral set of rules but a means of preserving a transcendent moral order.

Metaphors of Authority and Moral Hierarchy

One dominant theme in conservative judicial opinions is the metaphor of law as a reflection of a "higher" moral authority. In an abortion-adjacent decision, Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), which legalized same-sex marriage, Justice Samuel Alito warned that the decision imposed a "new orthodoxy" that disregarded millennia of moral wisdom. This language echoes Catholic natural law’s emphasis on continuity with historical moral traditions. Chief Justice John Roberts’ dissent argues that the Court should not "redefine" marriage, suggesting that legal definitions must align with an immutable moral reality.

Justice Clarence Thomas extends this logic further, framing constitutional rights within a natural law tradition. In his Obergefell dissent, he argued that dignity is an inherent quality given by God, not something the government grants or takes away. He invokes historical injustices, such as slavery and internment camps, to claim that external conditions do not alter one's fundamental dignity—a concept rooted in Catholic teachings on human worth.

However, nowhere is conservative Catholic reasoning more apparent than in abortion jurisprudence. Since the late 1960s, U.S. Supreme Court abortion cases have revealed a profound clash over morality, legal authority, and even the language of the law. Many conservative Catholic justices have drawn on natural law reasoning—the idea of an objective moral order (for example, the sanctity of life)—and vivid metaphors to frame their arguments. This is evident from the early privacy precedent of Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) through Roe v. Wade (1973) and its progeny, up to the seismic change in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022). Below, I analyze major abortion-related decisions, focusing on how conservative Catholic justices (in dissents or majorities) deployed language about morality, hierarchy, and authority.

Roe v. Wade (1973): “Raw Judicial Power” vs. Natural Moral Order

In Roe v. Wade (1973), the Court recognized a constitutional right to abortion before fetal viability, grounding it in the right to privacy. The dissents, however, framed this as an illegitimate moral choice by the Court, using striking language. Justice Byron White’s dissent (joined by Justice Rehnquist) accused the Roe majority of an activist overreach: he famously called the decision “an exercise of raw judicial power” and “an improvident and extravagant exercise of the power of judicial review.” White argued the Court had usurped authority properly belonging to the people, imposing its values about abortion. He wrote: “The Court apparently values the convenience of the pregnant mother more than the continued existence and development of the life or potential life that she carries.” This metaphor—weighing a mother’s convenience against a fetus’s life—conveys White’s view that the Court had unjustly elevated one moral interest over another. He further objected that nothing in the Constitution authorized judges to “impos[e] such an order of priorities on the people and legislatures of the States.” In his view, Roe was not a neutral adjudication but a moral decree: it “interpos[ed] a constitutional barrier to state efforts to protect human life” and gave mothers and doctors “the constitutionally protected right to exterminate [that life].” Such forceful words (e.g., exterminate) expose the natural law perspective that abortion is the taking of innocent human life. Justice Rehnquist’s separate dissent likewise criticized Roe’s reasoning as lacking constitutional foundation, though in drier terms.

White’s rhetoric in Roe set a template for conservative critiques. By invoking raw judicial power and contrasting the mother’s convenience vs. the life…she carries, he cast the Court as having upset the natural moral hierarchy (the inherent value of unborn life) and the constitutional hierarchy (the people’s authority to decide sensitive issues). This value-laden language signaled that, in his view, the Court had ventured beyond law into moral policymaking. Notably, White was not himself Catholic, but his dissent aligned with traditional Catholic natural law ideals regarding the protection of unborn life. His stance foreshadowed how later Catholic justices would frame abortion as a moral question that courts should not remove from the democratic process.

Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992): Morality, “Mystery,” and Scathing Dissent

Two decades later, Planned Parenthood v. Casey reaffirmed Roe’s core holding but allowed more regulation, replacing Roe’s trimester framework with the undue burden standard/metaphor. The Casey plurality (co-authored by Justice Anthony Kennedy—a conservative Catholic—along with Justices O’Connor and Souter) acknowledged the gravity of the abortion issue in almost spiritual terms. They wrote that “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life” (505 U.S. 833, 851). This often-quoted mystery of life passage suggests that each individual’s moral choices, including whether to carry a pregnancy to term, are central to personal dignity and autonomy. In effect, the plurality framed the abortion decision as deeply personal—a stance arguably rooted in a kind of individual natural law (personal conscience) rather than external moral authority—a problematic stance to address at another time.

The dissenters in Casey, however, especially Justice Antonin Scalia, vehemently rejected the plurality’s philosophical approach. Scalia, a devout Catholic, penned an incisive dissent arguing that the Court has no business making this moral choice for the country. He ridiculed the mystery of life rationale as “so exalted” that it obscured the actual legal question. Scalia’s view was that abortion policy should be decided through ordinary democratic means, not constitutionalized. He writes: “The permissibility of abortion, and the limitations upon it, are to be resolved like most important questions in our democracy: by citizens trying to persuade one another and then voting.” In other words, he invoked the metaphor of the public forum—a place where free citizens debate moral questions—as the proper venue for abortion policy, implicitly contrasting it with the imposed moral order of Roe.

Scalia’s dissent bristles with frames of moral authority and tradition. He argues that Roe and Casey “foreclos[e] all democratic outlet for the deep passions this issue arouses,” thereby “banishing the issue from the political forum” and “prolong[ing] and intensif[ying] the anguish” of the national debate. Here, the Court is metaphorically a barrier or dam blocking the natural flow of democratic resolution, causing pressure to build. Scalia bluntly concludes: “We should get out of this area, where we have no right to be, and where we do neither ourselves nor the country any good by remaining.” This memorable line casts the Court as an interloper in a domain reserved for the people—reinforcing a hierarchy in which elected lawmakers, not life-tenured judges, hold ultimate authority over contentious moral legislation.

To drive home his point, Scalia draws an analogy between Roe and the infamous Dred Scott decision, which sought to settle the slavery controversy. He noted that no Court decree could “end national division” on an issue “involving life and death, freedom and subjugation,” just as the Court could not simply dictate an end to the slavery debate. The implicit comparison of abortion to slavery—both seen as profound moral wrongs by their opponents—underscores how Scalia (and those who joined him, like Justice Clarence Thomas) viewed abortion through a natural law lens: as an issue of fundamental rights and wrongs that transcend what the Court alone should decide. Scalia also lambasted the Casey plurality’s reasoning as bereft of traditional legal support, noting that Roe “sought to establish—in the teeth of a clear, contrary tradition—a value found nowhere in the constitutional text.” Using the idiom “in the teeth of” (meaning directly against) tradition, he highlights how Roe defied the historic moral consensus that had criminalized abortion. In Scalia’s view, the Constitution does not enact any one theory of morality; absent clear text, the states must be free to follow their own moral judgments—a principle very much in line with Catholic natural law theory that positive law should not contravene long-standing moral norms.

It’s worth noting that Justice Kennedy, despite his role in the Casey plurality, often reflected Catholic-influenced moral reasoning in other abortion cases (as we’ll see in Gonzales v. Carhart). But in Casey, it was Scalia’s dissent (joined by Rehnquist, White, and Thomas) that voiced the clearest natural-law-style critique, condemning the Court’s value-laden pronouncements and insisting on deference to the moral choices of the people.

Gonzales v. Carhart (2007): Paternalism, “Baby” Metaphors, and Moral Authority

Gonzales v. Carhart upheld the federal Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003, marking the first time the Court banned a specific abortion procedure (intact D&E) with no exception for the woman’s health. The 5–4 majority was written by Justice Anthony Kennedy (a conservative Catholic), and it is notable for its visceral moral language and metaphors about the fetus and motherhood. Unlike Roe and Casey, which centers on rights and abstract principles, Gonzales reads as steeped in natural law notions of protecting life and maternal dignity.

Justice Kennedy’s opinion describes the banned procedure in graphic detail and asserts the government’s legitimate interest in fostering respect for fetal life and motherhood. One often-cited line from his opinion is: “Respect for human life finds an ultimate expression in the bond of love the mother has for her child. The Act recognizes this reality as well.” This metaphor of the maternal bond of love elevates a natural, almost sacred relationship between mother and unborn child—a relationship the government may vindicate by prohibiting especially brutal abortion methods. By characterizing that bond as the ultimate expression of respect for life, Kennedy’s opinion implies that certain choices (here, a late-term abortion method) offend an almost pre-political moral truth about motherhood and the value of life.

The Gonzales majority also explicitly discusses the moral and emotional consequences of abortion for women in paternalistic tones. Citing the record, Kennedy writes that “Whether to have an abortion requires a difficult and painful moral decision” and that “some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained,” with “Severe depression and loss of esteem” sometimes following. Referring to the fetus as “the infant life” and the woman “created and sustained” is a striking choice of words—infantilizing the fetus (literally calling it an infant) and emphasizing the mother’s natural role as life-giver and caretaker. This aligns with a conservative natural law perspective that from conception onward, we are dealing with a child, not just tissue. The Court went so far as to suggest that the ban on the procedure might protect women from making a decision they will regret: “It is self-evident that a mother who comes to regret her choice to abort must struggle with grief more anguished and sorrow more profound when she learns, only after the event, what she once did not know: that she allowed a doctor to pierce the skull and vacuum the fast-developing brain of her unborn child, a child assuming the human form.” This extraordinary passage—graphic in its description of the procedure—serves as a moral narrative. It paints the woman as a loving mother, the fetus as a baby (the unborn child explicitly assuming the human form), and the abortion as horrific violence done partly in ignorance. The metaphorical framing here is unmistakable. Abortion, at least via this method, is likened to infanticide (pierc[ing] the skull of a child), and the law is cast as a protector of both the fetus and the mother’s conscience.

Such language had rarely (if ever) appeared in a Supreme Court majority opinion on abortion before Gonzales. It reflects a natural law reasoning in the sense that the opinion appeals to inherent truths about human life and motherhood rather than purely secular or procedural justifications. The majority approvingly noted that Congress sought to “draw a bright line that clearly distinguishes abortion and infanticide,” given the “disturbing similarity to the killing of a newborn infant” in the banned procedure. By endorsing this bright line metaphor, the conservative justices signaled that the law can and should mark a moral boundary to prevent society from sliding down a slippery slope of devaluing life, even referencing the Court’s own precedent in Glucksberg on assisted suicide and the path to euthanasia.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissent in Gonzales criticizes the majority for its patronizing attitude toward women and for abandoning the health exception precedent of Stenberg v. Carhart (2000). But from a linguistic standpoint, Gonzales exemplifies how the Court’s conservative Catholic bloc (Kennedy, joined by Scalia, Thomas, Roberts, and Alito) uses emotionally charged, value-oriented language to justify abortion restrictions. They couch the state’s interest in terms of protecting the integrity of the medical profession and the conscience of society. In one passage, the Court emphasizes that the state may use its regulatory power “in furtherance of its legitimate interests in regulating the medical profession in order to promote respect for life, including life of the unborn.” The phrase, promote respect for life, including life of the unborn, captures the essence of the natural law argument. The law should uphold respect for innocent human life as a fundamental value. Here, the hierarchy invoked is that the moral value of life can usurp individual choice in certain cases and that the legislature, as the people’s moral agent, has the authority to express this value.

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022): Tradition, “Innocent Life,” and Returning Authority to the People

Finally, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Org. (2022), the Supreme Court’s conservative majority—which included six Catholic justices at the time—overturned Roe and Casey entirely. Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion is firmly rooted in so-called constitutional originalism and historical analysis, but it also reflects the moral-metaphorical framing that earlier dissents pioneered. The very opening lines of Dobbs acknowledge the profound moral dimension of the issue: “Abortion presents a profound moral issue on which Americans hold sharply conflicting views. Some believe fervently that a human person comes into being at conception and that abortion ends an innocent life. Others feel just as strongly that any regulation of abortion invades a woman’s right to control her own body…” By starting this way, the opinion treats the case as a culture-defining moral conflict. Notably, the text validates both perspectives as deeply held, including the view that abortion “ends an innocent life,” a phrase that echoes natural law (the innocence of the unborn) and religious rhetoric. This set the stage for the Court’s conclusion that the Constitution itself is neutral on abortion, thereby permitting states to decide which moral view to enact.

Throughout Dobbs, Alito emphasizes history, tradition, and the limits of judicial power—themes long argued by Catholic justices like Scalia and Thomas. He repeatedly criticizes Roe as an unwarranted judicial intervention into a contested moral issue. For instance, citing Justice White’s 1973 dissent, Alito calls Roe “the exercise of raw judicial power” that “sparked a national controversy that has embittered our political culture for a half century.” The explicit reference to raw judicial power (quoting White) shows the majority aligning itself with that earlier critique: namely, that Roe was an abuse of the Court’s authority, untethered from the Constitution and inconsistent with the natural moral order as perceived by good (White, Christian) Americans. By invoking this phrase, Alito frames the Dobbs Court as correcting an error and restoring proper hierarchy. The Court would no longer override the moral decisions of the people.

A key metaphor in Dobbs is the idea that Roe and Casey “short-circuited” the democratic process. The majority noted that Roe “effectively struck down the abortion laws of every single State” and “short-circuited the democratic process” by closing debate and forbidding Americans from deciding the issue through their elected representatives. The term short-circuited evokes an image of a process unexpectedly cut off. In other words, the normal political circuit was bypassed by the Court’s fiat. Similarly, Alito wrote that the Court “cannot bring about the permanent resolution of a rancorous national controversy simply by dictating a settlement and telling the people to move on.” This vivid phrasing—the Court dictating and telling the people to move on— displays the majority’s view that Roe/Casey was an improper top-down mandate on a moral question. It resonates with Scalia’s point in Casey that such issues cannot be settled by “judicial diktat.” The Dobbs Court essentially said that fifty years of experience proved the point: Roe did not settle anything, and it’s not the Court’s role to settle moral debates by edict.

Most importantly, Dobbs reorders the hierarchy of decision-making on abortion. The opinion’s concluding holding is unequivocal: “The Constitution does not confer a right to abortion. Roe and Casey must be overruled, and the authority to regulate abortion must be returned to the people and their elected representatives.” The choice of words, returned to the people, frames it as a restoration of rightful authority, almost a corrective justice. This reflects a longstanding argument by conservative justices that Roe took the issue AWAY from the people without constitutional justification. Now, by overruling Roe, the Court was, in its view, restoring the natural order of things: moral questions like abortion should be settled in the political arena. Chief Justice John Roberts (also Catholic), in a concurring opinion, takes a more incremental approach (he would stop short of overturning Roe outright), but even he agreed that the viability line from Roe/Casey was arbitrary and not grounded in the Constitution.

Justice Thomas, in a concurring opinion in Dobbs, goes further to question the entire doctrine of substantive due process and suggests revisiting other precedents. Though, the majority downplays this. Justice Brett Kavanaugh (Catholic) wrote separately to emphasize that Dobbs does not outlaw abortion nationally but leaves the decision to each state. Kavanaugh echoed the neutrality principle, writing that the Constitution is “neither pro-life nor pro-choice on the issue of abortion” and that Roe had improperly “took sides on a consequential moral question” by removing the issue from democratic debate. This notion of court-enforced neutrality can itself be seen as rooted in a kind of natural law humility (i.e., that when the Constitution is silent, the law should not contradict the natural ability of communities to legislate their moral values).

In sum, the Dobbs majority opinion uses less overtly emotive language than Justice Kennedy’s Gonzales opinion. However, it still affirms the same foundational ideas that conservative Catholic justices had voiced for years: that abortion involves “profound moral” considerations and the taking of innocent life and that unelected judges should not override the longstanding traditions and ethical choices of the community. By repeatedly referencing the historical criminalization of abortion and the lack of support for Roe in constitutional text or history, Dobbs grounded itself in the idea that the natural condition (legally and morally) is for societies to be free to protect unborn life. The decision explicitly overruled the erroneous precedent of Roe, which it described as “egregiously wrong from the start” (a blunt moral judgment as much as a legal one).

Language of Life, Morality, and Authority

Across these cases, conservative Catholic justices leverage language to imbue legal arguments with moral weight. They often treat the fetus as a rights-bearing entity, using terms like unborn child or infant life, invoke the sanctity of life and natural maternal instincts, and deplore what they view as the judiciary’s usurpation of moral decisions. Their metaphors frequently establish a hierarchy:

divine or natural moral law → democratic will of the people → judicial pronouncements.

For example, Justice White in Roe warned against judges imposing an “order of priorities” on fundamental values without constitutional warrant. Justice Scalia in Casey urged returning authority to where “we have no right to be” to the people. By Dobbs, these views became the Court’s majority stance: the opinion stresses that it is not exercising “raw power” but instead restoring the decision to the polity.

The above analysis reveals a consistent thread: conservative opinions use moral and naturalistic metaphors to frame abortion as a question of fundamental ethics and social order. Whether it’s describing the womb in terms of the bond of love and grave moral decisions (Gonzales) or cautioning that the Court cannot dictate answers to rancorous moral conflicts (Dobbs), these justices infuse their judicial writing with a sense of higher law and rightful authority while disingenuously disavowing their right to authority in private life. On the other side, supporters of abortion rights, including some Catholic justices like William Brennan in Roe, and the Casey plurality to an extent) used the language of privacy, liberty, and personal autonomy, metaphors of self-determination and equality. However, it was the moral-hierarchical framing by the conservative wing that ultimately prevailed in Dobbs. The Court’s new majority, heavily influenced by Catholic jurists, essentially adopted the view that Roe had “taken sides” improperly and that the Constitution allows Americans to embody their natural law convictions in abortion policy (be that protecting “innocent life” or permitting early abortions).

Each of the landmark cases—Roe, Casey, Gonzales, and Dobbs—thus showcases how metaphor and moral reasoning are wielded in abortion jurisprudence. Conservative Catholic justices, in particular, have not hesitated to use moral language (e.g., “protect human life,” “exterminate it,” “innocent life,” “profound moral issue”) and imagery of hierarchy (judicial usurpation vs. democratic choice; mother vs. child; civilization vs. barbarism) to argue their point. These rhetorical choices are deeply intertwined with their legal reasoning. In their view, the Constitution should be interpreted in line with the Nation’s history and the “laws of nature”—which include an understanding of the value of unborn life—and the role of the Court is to uphold those principles or step aside and let the people decide. The result is a body of Supreme Court opinions on abortion that read as a dialogue about natural law, moral truth, and the proper locus of societal decision-making.

Religious Liberty and the Right to Moral Conscience

If you are not convinced of the role of Catholic doctrine in SCOTUS decision-making, there are additional non-abortion-related metaphors to explore that add broader context to the abortion issue’s framing.

Conservative justices’ commitment to natural law extends to their defense of religious liberty. In Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014), the Court ruled that a business owner’s religious objections to contraception could override federal regulations. The majority opinion, written by Justice Alito, positioned religious conscience as paramount, reflecting Catholic teachings on the primacy of moral duty over civil law. Similarly, in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022), the Court upheld a high school football coach’s right to pray on the field, reinforcing a metaphor of religious expression as a fundamental pillar of moral order.

Justice Alito has been outspoken about what he sees as a growing "hostility to religion" in legal and cultural spheres. He argues that religious liberty is foundational and warns that its erosion threatens the moral underpinnings of American society. His rhetoric frames faith as a pillar of social stability, a perspective deeply tied to Catholic natural law’s vision of a morally ordered world.

The Far-Right Catholic Vision for America’s Future

The Supreme Court’s conservative Catholic majority is not simply interpreting the law—they are fundamentally reshaping the legal framework of the United States to align with a theocratic worldview. Their reliance on natural law reasoning, their affiliations with far-right Catholic networks, and their alignment with authoritarian nationalist figures like Trump and Vance suggest that their jurisprudence is not about constitutional originalism—it is about moral imposition. The Court’s abortion rulings are not isolated decisions; they represent a broader effort to redefine the relationship between the state and the individual, where the law serves as a tool for enforcing religious moral doctrine rather than protecting individual liberty. If this trend continues, it will not stop with abortion, affirmative action, or other complex social issues. The same reasoning used to overturn Roe v. Wade can be deployed against contraception, same-sex marriage, and even broader civil liberties under the guise of restoring "moral order." This is not just a legal battle—it is a fight for the soul of American democracy, where the stakes are nothing less than the preservation of secular governance against an encroaching theocratic vision. Reject this vision that is fundamentally at odds with democracy.

Sources:

- Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. 682 (2014).

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 597 U.S. (2022).

- Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007).

- Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965).

- Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 597 U.S. (2022).

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 (2015).

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 914 (2000).

Further reading:

Gore, Gareth. 2024. Opus: The Cult of Dark Money, Human Trafficking, and Right-Wing Conspiracy Inside the Catholic Church. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Green, Steven K. 2023. "Religion and the Supreme Court." Pp. 450-465 in The Routledge Handbook of Political Science, edited by M. Smith and J. Doe. New York: Routledge.

This week in metaphor

The “human costs” of climate change.

The phrase "human costs" makes suffering sound like an expense, as if lives can be tallied up like a financial report. It’s a common way to talk about disasters, war, and policy decisions, but it comes with problems.

For one, it reduces people to numbers, ignoring emotional and cultural losses. It also makes suffering seem like an unavoidable trade-off, something to be "managed" rather than prevented. Worst of all, it can desensitize us, turning tragedies into statistics.

There are better ways to say it. How about"burden on communities?" Shift the focus to real people rather than costs on a balance sheet. While "human costs" is attention-grabbing, we should be careful about what it implies. Suffering isn’t just a price to pay—it’s something we should work to prevent. There is no acceptable expenditure when it comes to human life.