The Extended Case: Burawoy’s Vision of Sociology in Motion

Dedicated to Tyler Leeds, a kind friend, colleague, and Michael Burawoy's last student.

Michael Burawoy (1947–2025) invigorated our sociological imagination by presenting production as a site of political contestation, framing consent as a construct shaped by institutional practices, and viewing sociology as inherently engaged with public life. His work translated abstract theoretical frameworks into a language that resonated with everyday experience, much like a metaphor connects individuals to broader conceptual realms. Across The Politics of Production, Manufacturing Consent, Public Sociology, and over 400 other publications, he drew parallels between familiar domains and the multifaceted realities of social life. He urged us to see production as a battleground for political power rather than a mere economic process, consent as something forged through social rituals rather than passively given, and sociology as a discipline committed to the accountability of our institutions. His way with metaphor made this possible.

In a 2018 podcast appearance on Focus on Flowers,[1] he remarked that labor on the steel floor was not just about work but about creating an image—a promise of egalitarian, just, and efficient socialism—even as the actual conditions were marked by inequality and inefficiency. His colleagues, by laughing at the gap between ideological promise and lived reality, were not just complaining; they were calling for the state party to honor its commitments. This moment encapsulates a core aspect of sociology. It reveales how a critical awareness of society emerges through both theoretical reflection and everyday experience. Burawoy’s genius was in demonstrating that ideology does not exist in the abstract—it is something produced, enacted, contested, and ultimately extended through the structures of daily life.

The power of Burawoy’s insights often lay in his ability to stretch conceptual boundaries through metaphor. This ability is plainly clear in his methodological innovation: the Extended Case Method. The phrase itself—“extended case”—is more than a technical term. It is a conceptual metaphor that fundamentally reshapes how we understand ethnography. By evoking “extension,” Burawoy reframes the practice of fieldwork not as a static description of a bounded site but as an expanding, evolving, and deeply engaged process. Just as he argued that labor practices extend beyond the factory floor into broader ideological and political struggles, so too did he argue that ethnographic cases extend outward into history, theory, and social structure.

The Extended Case Method Metaphor

The phrase “extended case” structures our understanding of ethnography by evoking movement—continuity, connection, and outward expansion. Burawoy’s methodological metaphor invites us to think beyond the immediate, beyond the fixed boundaries of a research site and instead embrace ethnography as a practice of following connections wherever they lead. Just as he traced shop-floor interactions into state policy and the ideological struggles of global socialism, ethnography, in his view, must move outward, capturing the larger social forces that shape even the most localized experiences. This spatial extension pushes the researcher to recognize that no social phenomenon exists in isolation. Every case is embedded in wider structures of power, economy, and politics.

But movement in space is only part of the story. For Burawoy, a case is never just about the present moment—it carries the weight of history and the seeds of future transformation. This temporal extension says that no ethnographic site can be fully understood without tracing its historical lineage and anticipating its possible trajectories. The factory floor is never just a workplace. It is the product of past labor struggles, economic shifts, and ideological battles, and it is also a space where future social change is being negotiated, whether through quiet resistance or outright contestation. Beyond capturing connections across space and time, the extended case method reimagines the very purpose of ethnography. Conventional case studies often aim to confirm theoretical frameworks, treating fieldwork as a means of applying or testing established ideas. Burawoy’s vision, however, turns this logic on its head. Theoretical extension means that the case does not simply describe reality—it actively restructures our understanding of it. Theory is not a static framework but a living, evolving entity that must be stretched, challenged, and reworked in response to what the field reveals. The act of extending a case is, in itself, an act of theoretical transformation. Yet, this process is not a solitary endeavor. The extended case method insists on dialogical extension, positioning the researcher as an active participant in an ongoing conversation—both with those in the field and with the scholarly traditions that precede them. Ethnographic knowledge, in this sense, is never produced in isolation. It emerges through engagement, through recursive dialogue, through a back-and-forth process of interpreting, refining, and extending knowledge in new directions.

Each of these dimensions—spatial, temporal, theoretical, and dialogical—embodies Burawoy’s broader sociological vision. His ethnographies were not just descriptions of social life but interventions into it, showing how the micro is always entangled with the macro, how the present is always shaped by history, and how theory must always be in motion. The metaphor of extension captures the essence of his intellectual project, reframing ethnography as a dynamic, iterative, and deeply engaged process rather than a static act of observation. Through this lens, fieldwork becomes more than a methodological tool—it becomes a way of seeing the world as constantly unfolding, interwoven, and subject to transformation.

Burawoy’s Legacy: Sociology as an Expanding, Engaged Discipline

Michael Burawoy’s work transformed the way we think about both sociology and ethnography. His methodological innovations were never just about research techniques—they reflected a broader vision of sociology as a discipline that intervenes in public life, critiques power, and remains reflexively aware of its theoretical commitments. The metaphor of the Extended Case Method embodies this ethos. It suggests that knowledge is not static but is something that must be continuously pushed forward—expanded through history, elaborated through dialogue, and stretched into new theoretical and political terrains.

The first time I read Burawoy as an undergraduate at Berkeley, and later as a graduate student, I was struck by the energy with which he extended sociology beyond its conventional boundaries. His work and legacy challenge us to think critically about how institutions shape ideology, how labor produces not just goods but belief systems, and how ethnography can serve as a tool for both understanding and transforming the world. He showed us that sociology does not merely observe—it extends. And that is a legacy worth carrying forward.

Further Reading

Burawoy, Michael. 1998. "The Extended Case Method." Sociological Theory 16(1):4–33.

“Remembering Michael Burawoy: A True Inspiration for 21st Century Sociologists,” Jos Chathukulam. Mainstream, Vol 63 No 6, February 8, 2025.

This week in metaphor

Hi, Schuyler here. Well, with a lot of news, we can expect a lot of metaphor. Here are three of my favorites from the week.

- Bianca Wylie's heartening post on “the politics of salvage”. Political salvage is kind of like wreckage, but with some hope. A reminder that, as we watch our institutions crumble, we can be preparing to do something with the pieces.

Reading up on the concept, I was reminded of a deeply moving piece by Tuan Andrew Nguyen entitled “The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon” which explores the salvaging of US bombs in rural Vietnam as a political and spiritual practice. May I suggest it as a beautiful distraction from your doomscrolling.

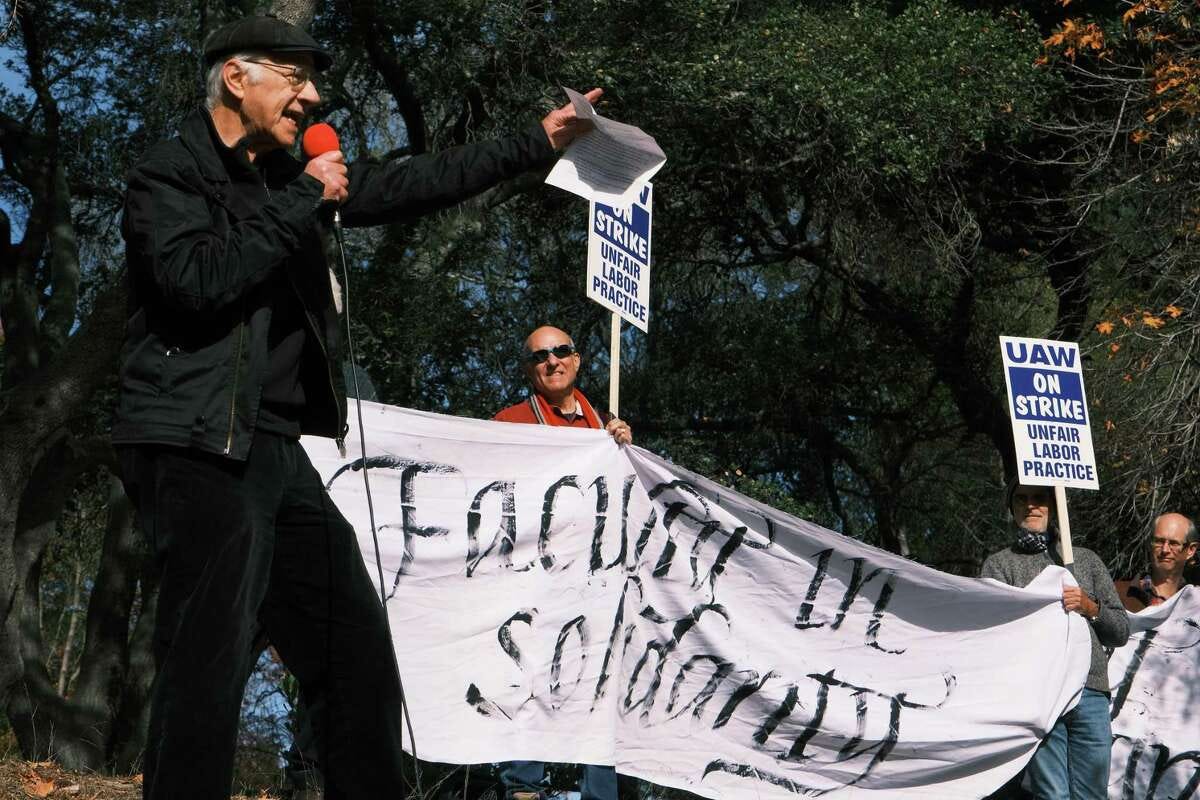

- Jesse Hagopian's framing of the proposed closure of the Department of Education as “educational arson” in this Democracy Now! interview. Remember that our house isn’t just burning, someone set it on fire.

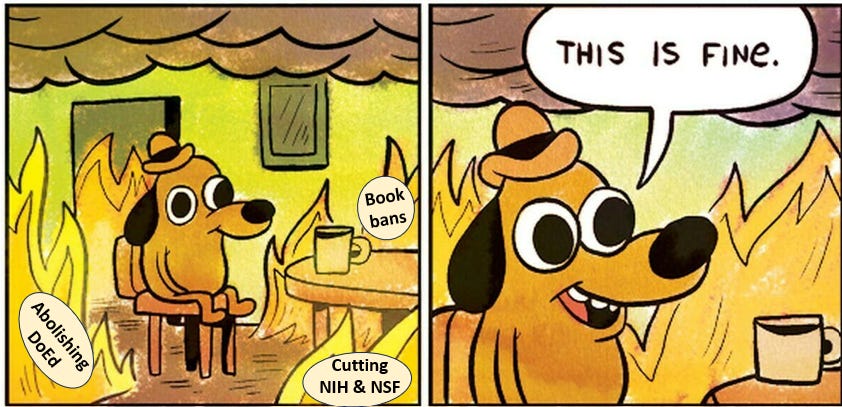

- And a reminder from Davos that we're all stuck on this terrifying journey together. Despite their acknowledging the stormy, turbulent, and unsettled waters ahead, you can be pretty sure that these unelected drivers aren't all that interested in looking for safer paths.

If you really enjoyed this piece, please consider leaving us a tip. We don't believe in paywalls and are as sick of paid subscriptions as you are. So we don't even offer them. But it does cost money to keep these projects going and anything you have to spare helps ❤️

[1] “And so there was a metaphor of what we were doing so much of our time on the steel floor was actually creating an image that we didn't believe in, that we were supposed to engage in a whole series of rituals that socialism was egalitarian, was just, was efficient, and yet all around us we saw inequality, injustice, and inefficiency.

And so there was a real contrast, and my fellow workers would always joke about that discrepancy between ideology and reality. I made the claim that in making that contrast, they were calling upon the party state to actually fulfill the promises that it gave to the population, the socialist promises. They were critical of the party state for not actually producing the socialism they pretended existed, and that therefore the working class, unlike in a capitalist country, it actually had a socialist consciousness.”