What's so "hard" about science?

When different voices and experiences are included in scientific research, a broadening occurs - we ask new questions and contextualize old facts. Is this "softening" or progress?

It's been a tough two weeks for academia, especially in the USA. The censorship announcements kept rolling out over social media, with claims that words like “victim”, “woman”, “diversity”, and “oppression” would now be banned in grant applications and government-funded applications. News first came about research in the sciences funded by the NSF and NIH and then from research in the humanities funded by the NEH (this order and division will be important later). We all[1] know this is bad, we all know this is a violation of our right to freedom of speech and thought, and we all know that this will impact some groups in academia (namely the ones we are no longer supposed to name) more than others (namely white heterosexual cis men). What this blog post is about is the logic that, for many, helps to legitimize this kind of censorship. I think the word “hard” can get us a surprisingly long way. I also think that by using the “hard-soft” disciplinary distinction, we may be perpetuating the legitimacy of this logic.

When I started seeing screenshots of banned words on social media, I went looking for source material, some kind of government document to which these particular word bannings could be traced. And what I found was this report, led by Ted Cruz (of course), entitled “Division. Extremism. Ideology. How the Biden-Harris NSF politicized science”. It’s an infuriating read, but an important one. The executive summary starts (emphasis added):

Since the beginning of the Biden-Harris administration, the National Science Foundation (NSF) has increasingly funded research and programs that color scientific investigation and engagement projects through the lens of political ideology, undermining objective hard science disciplines such as physics, chemistry, and biology in which facts and theories can be precisely measured, tested, and independently reproduced.

Objective hard science is what is under attack, and with it all of our measurable, testable, and reproducible facts.[2] We’re concerned with metaphor in this blog, so about that “hardness”… What is it exactly, and how does it contribute to our valuing of the fields, methods, and research topics in question?

“Hard”, at its most concrete (pun intended), refers to the solidity of an object’s surface. A hard object is one that is difficult to bend, break or penetrate.[3] As such, a hard object is also, in a sense, pure; in its impenetrable solidity, it is only itself, unadulterated by the mixing or absorption of other substances. This entailment of purity comes out in Teddy’s report, with democrats accused of “injecting bias” into scientific inquiry and “neo-Marxist” researchers accused of “inserting political considerations into the foundation of what should be apolitical scientific research”. The intended message - science is a pure object which is compromised if any social subjectivities are incorporated (reframed by Ted and friends as divisive political ideologies).

But how did the social get excluded from the scientific in the first place? And why is the social framed as the injected pollutant rendering our science impure? Well, spoiler, it’s mostly sexism. But let’s follow our metaphor first.

The word “soft” does not appear in Tedster’s report, but it is there, implicitly, as the antonym of “hard”. Soft things are bendable, moldable, and penetrable (see the sexism yet?). These are things that can change shape, that can look different in different physical contexts. Other objects and substances get stuck and tangled in soft things. Think play-doh, sweaters, your fluffy cat.[4]

One step of metonymy later, and we get to the hard-soft distinction as a stand in for difficulty (it is literally more difficult to bend/break/puncture a hard surface than a soft surface). “Hard jobs” take effort and skill, while “soft starts” let one ease into things. Take a metaphoric step instead, and we get to the hard-soft distinction as signaling degrees of emotionality and sensitivity (as opposed to rationality). “Going soft” means letting one’s emotions intrude on ones logical actions, and “cold hard facts” are those devoid of (and potentially opposed to) the subjectivities of personal experience and interpretations.

Put all these senses together and we get a hard-soft distinction that is deeply gendered. From idealizations of the male body has hard and muscular and the female body as soft and giving, to the assumption that men do the difficult work and women the easy (and emotional) work, to stereotypes of the overly sensitive woman and highly valued rational man. Men are associated with literal, metonymic, and metaphoric hardness, women with softness. And in our patriarchal society, the value judgements come in at every stage - hard is good and strong, soft is bad and weak.

Alright, that’s the backdrop. Now to the sciences.

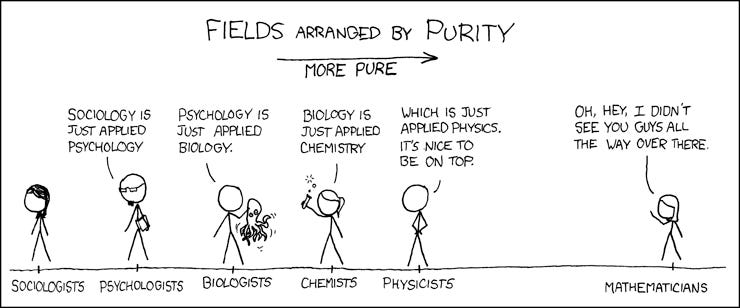

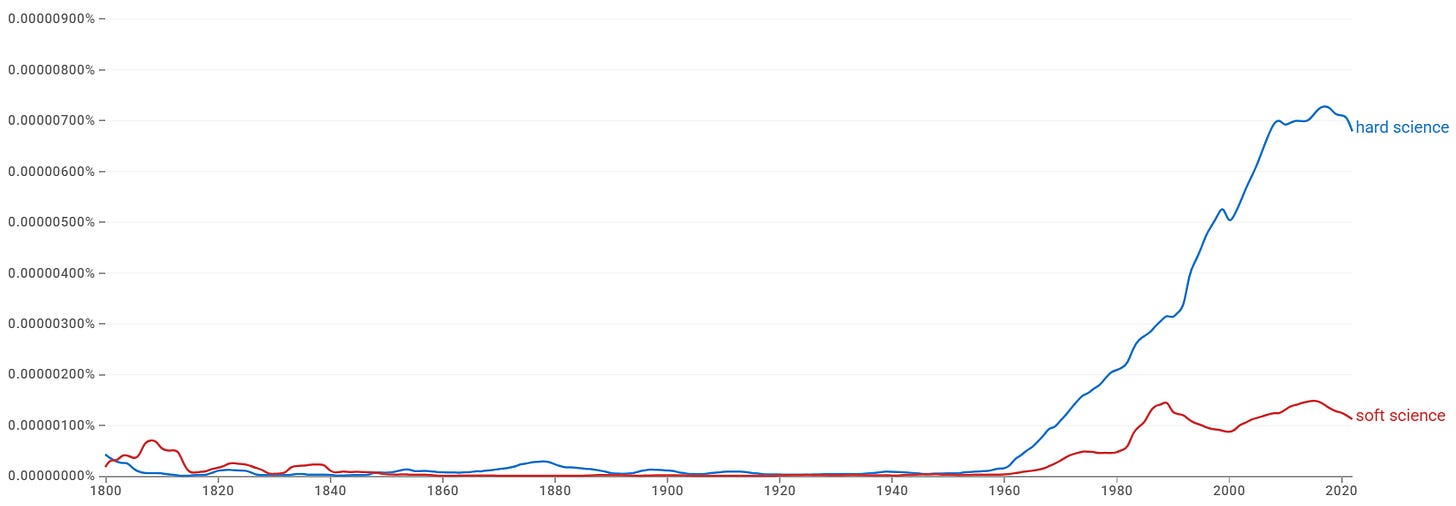

It seems we’ve been using the hard-soft distinction to differentiate between academic disciplines for a long time[5], but Shapin (2022) traces our modern use (and seeming obsession) to the US in the mid-twentieth century. The zeitgeist was this: technological advancements through engineering would fuel human progress, and the “hard” sciences (physics, chemistry, and biology) were there to solve the literal and metaphoric “hard” problems to enable these advancements.

Other disciplines like sociology, anthropology, political science, and economics, perhaps could contribute too, but this would be through social engineering, helping to better understand how to sell the public on these technological advancements. The “soft” sciences would deal with the hearts and minds, while the “hard” sciences did the real work.[6]

The functional proximity of the “hard” sciences to technology and engineering helps to explain the qualities we tend to attribute to them — there’s lots of math, precision, rigorous testing, and physical labs. The less math, fewer labs, and looser hypotheses you have, the further from engineering you must be; the softer you must be.

When social scientists became interested in this hard-soft distinction as a subject of study, the connection between hardness and progress was extended to disciplinary development. Shapin again:

the Harvard political scientist Don Price noted the conviction among “orthodox natural scientists” that “rigorous scientific method” was being “gradually extended from the hard sciences to the soft sciences,” that there was a natural progression toward hardness, and that the soft sciences might eventually catch up.

So, hard science deals with hard facts, ones you can hold, measure, and test; ones that, through their discovery, would help to solve the problems of the world through technological advancement. The soft sciences dealt in the messy soft facts of human behavior and society, full of exceptions and subject to interpretation. There was hope though that they could harden by developing sufficiently rigorous methodologies that would allow for the study and discovery of objective social, behavioral, and psychological realities.

We see some value judgements sneaking in already. The “soft” sciences are perceived as being less developed than the “hard” sciences. Their lack of rigor gets associated with a lack of seriousness, then with easiness.

Okay, oh, boo-hoo, the humanities and social sciences are underappreciated. We’ve been whining about that forever. What does this have to do with the censorship? Well, this is where gender comes in.

Let’s look at some “cold hard facts”.

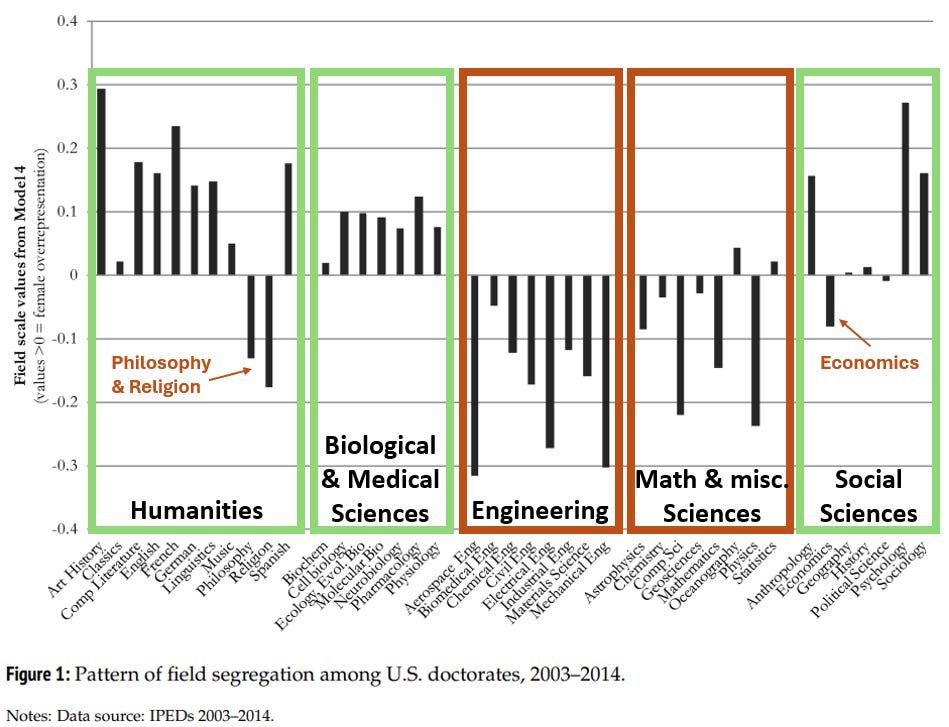

- Even though the enrollment of women in US higher-education has outpaced that of men, women are still over-represented in the “soft” sciences and under-represented in the “hard” sciences. (the exceptions? Philosophy, religion, and economics. Color me deeply unsurprised)

- The line between the “hard” and “soft” sciences shifts as more women get involved. Higher perceived participation of women in a field leads to a higher likelihood of categorizing the field as “soft”. Labeling a field as “soft” in turn leads to the perception that it is less rigorous and less deserving of federal funds.

- And indeed, those measured perceptions play out in the real world, as research done in disciplines "dominated by women" is consistently evaluated lower and receives less grant support.

Well, that sucks right. But, still, what does this have to do with censorship?

My argument is this: as science looks less like the hard white male ideal, the real white men in power get insecure. The “purity” of science is not scientific, it’s social.

When women, and people of color, and disabled people, and trans folks, and queer comrades get into these spaces, they bring with them experiences that challenge the whole hard and pure narrative that scientific “progress” is built on. Pure hard (white male) science has done incredible things, but it has also fucked up a lot (e.g. I don’t love having “an unused crayon’s” worth of microplastics in my brain). And when the people most fucked over finally get into the lab, they’re gonna point that out!

That disruption is, unsurprisingly, unwelcome. That disruption says, hey, all of that rigorous methodology, all of that math, all of that testing, that rational logical scientific “view-from-nowhere”? It isn’t enough. It missed so much. It missed so much harm and so much potential to do good.

And accepting that accusation? Well, that would be the sciences going soft. And there’s no way Project 2025 is letting that happen.

Embrace or resist?

Definitely resist, and resist hard.

In my home discipline of linguistics (housed randomly in either the humanities or social sciences depending on what university you ask), I’ve seen the virtue of hardening go largely unquestioned. This is seen in hiring and funding patterns where computational and experimental approaches are subtly or not-so-subtly granted higher prestige, and in peer-review procedures where careful qualitative approaches are rejected or excluded from consideration (looking at you Discourse & Society…). Linguistics, like so many other “soft” fields, has fallen for the white male virtue of “hardness”.

To be clear, I do not mean to suggest that computational and experimental approaches are bad, or that they shouldn’t be done. They’re great, and definitely should be done! Heck, I do experimental work sometimes. What I am saying is that leaning in and pointing to these methods as indications of “progress” has big girlboss energy. You can’t dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools.

We’re not going to save ourselves by being as “hard” as the “hard” sciences. We’re going to save ourselves and everybody friggin’ else by rejecting the rhetoric of white male purity.

This week in metaphor

And now some tasty metaphor tapas. Here’s a couple of my favorite found metaphors of the week:

- The following absurd image from Brigitte Nerlich, inspired by a quote in the NYT framing the pitiful attempts at AI regulation as “policymakers on horseback, struggling to install seatbelts on a passing Lamborghini.”

- M*sks’s new favorite game of “deleting” governmental institutions. This caught my eye because, well, it’s horrifying. But also because the metaphor indicates a big epistemic shift. We spent a long time trying to get our heads around computers by piling on office metaphors (i.e. your computer’s desktop, folders, and recycling bin). But we’re in the digital age now, baby, pulling our computer language into real life and forgetting the real consequences.

That’s all for now. Thank you for reading!

May the metaphors be with you ✊

- Schuyler

If you really enjoyed this piece, please consider leaving us a tip. We don't believe in paywalls and are as sick of paid subscriptions as you are. So we don't even offer them. But it does cost money to keep this thing going and anything you have to spare helps ❤️

[1] Where “we” here restricts the meaning of “all” to the type of people most likely to read this blog post.

[2] Notice how clever this is. The left has been loudly denouncing science denialism since the start of Tr*mp’s first presidency. Now we see the right co-opting that (apparent) valuing of scientific fact in their own rhetoric.

[3] I really hate this word, but it’s unfortunately a part of the story.

[4] Though cats are arguably liquid… I know, the joke is now 10 years old. We have to look back that far for comic relief. Sorry.

[5] Auguste Comte’s nineteenth-century “hierarchy of the sciences” is the thing I see cited most frequently as the beginning of all this, which was then re-vamped and hyped-up by Stephen Cole a hundred years later.

[6] Shapin notes that the hard-soft distinction is used somewhat differently and sporadically during earlier periods, such as by 16th century English humanists who lumped oratory in with the hard sciences.